Cast: Tahar Rahim, Niels Arestrup, Adel Bencherif

Jacques Audiard is perhaps the only filmmaker working today whose cannon of films can be uttered in the same breath as those of Melville and Chabrol. Like those giants of the Nouvelle Vague, Audiard is a master of the thriller/ crime genre and has spent the best part of his career unpicking its tightly knit conventions and tropes to create some of the most affecting and unforgettable films of the past few decades.

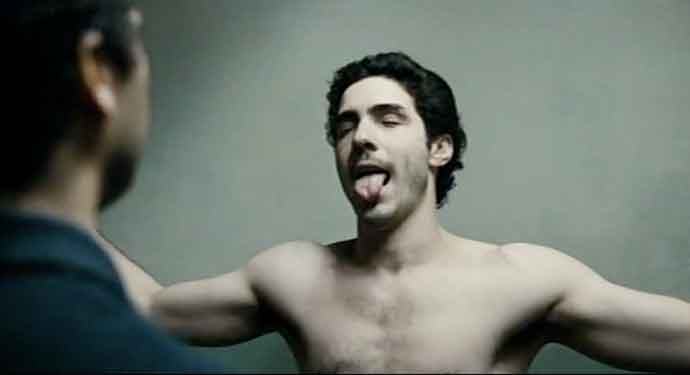

‘A Prophet’ tells the story of Malik (Rahim), a French Arab of North African descent embarking on a six-year sentence in a French jail. The prison is ruled by Cesar Luciani (Arestrup) and his Corsican gang; so when they approach Malik with an offer to accept him into the gang if he murders an unruly Arab inmate, it is clear that this is not an offer he can refuse. Malik is made a lieutenant in the gang after committing the gruesome act – and we are not spared a single detail, from Malik’s agonising attempts to conceal a bare razor blade in his mouth to the pathetic gurgling screams of the unfortunate Reyeb.

Things do not improve for this unfortunate outsider, however, as he is slanted by the Corsicans (who call him ‘Arab’ and suggest he is only fit for belly-dancing and house-work), berated by the Arabic community in the prison for siding with the enemy, and haunted by Reyeb’s ghost as he lies alone in his murky cell. Malik teaches himself to read and, by carefully studying Cesar and the gang, learns to speak Corsican and slowly picks up the ins-and-outs of the gang’s operations. He also makes an ally in Ryad, a softly spoken man with the cold, dark eyes of a killer.

Malik works his way up the chain of command to become Cesar’s right-hand man and most trusted ally in the prison; and when Cesar organises for him to be released for one day (to check on Cesar’s interests on the outside) he uses the opportunity to start up a side-business moving vast packages of hasish with Ryad (who has since been released) between France and Spain. As Cesar becomes a more desperate and alienated figure in his cell, and powerful adversaries work up the courage to confront him, Malik benefits from all the new connections he is making.

One of the founding tenets of the Nouvelle Vague was an admiration for American film noir, and a mystical ability to inject that rigid genre with a flowing, intuitive, philosophical dimension. Melville, Chabrol, Godard, et al were open about their worship of Humphrey Bogart, John Huston, and the other legends of Hollywood noir; but they were all cineastes and academics who knew that the ‘camera-stylo’ could be used for so much more than Dashiell Hammett adaptations.

In ‘A Prophet’, Audiard has created an accessible and stomach-churning prison drama that the most cautious American viewer could enjoy. All the genre tropes are there – gang initiation, deceit, loyalty, criminal codes, corrupt authorities, car chases, gun battles – but these comforting and visceral moments only exist as sharp jabs to the stomach in what is actually a flowing, complex study of loneliness and masculinity. There is no attempt to validate Malik as a hero, he, along with every other character in the film, is a victim of the brutality they were born into. There is no hope, just a daily fight to survive and make tomorrow’s fight a bit easier. When Ryad develops a terminal disease, there is no despair or sadness shared between these two close friends, just an understanding that Ryad will be released from his bondage slightly sooner than Malik.

Having worked with some of the biggest stars in French cinema (namely Jean-Louis Trintignant, Mathieu Kassovitz, and Vincent Cassel) Audiard has chosen a relative unknown to lead this brutal character study. Tahar Rahim’s performance is without a doubt one of the most infecting and memorable performances of the year. He creates a perfectly conflicted and tragic figure in Malik: he is cold and toughened by a lifetime in the penal system, but he has a child-like vulnerability and a need for human connection. His friendship with Ryad is perfectly portrayed… a deep affection that can never be admitted by either party.

This is undoubtedly one of the finest films of the year. It is an inspiring proof that the genre conventions of American story-telling can be fused with the mystifying explorations of the human condition more present in European independent cinema, to create films that perhaps rise above both camps purely because they are capable of fulfilling the highest aims of culture and communication… to inform, educate, and entertain.

Jacques Audiard is perhaps the only filmmaker working today whose cannon of films can be uttered in the same breath as those of Melville and Chabrol. Like those giants of the Nouvelle Vague, Audiard is a master of the thriller/ crime genre and has spent the best part of his career unpicking its tightly knit conventions and tropes to create some of the most affecting and unforgettable films of the past few decades.

‘A Prophet’ tells the story of Malik (Rahim), a French Arab of North African descent embarking on a six-year sentence in a French jail. The prison is ruled by Cesar Luciani (Arestrup) and his Corsican gang; so when they approach Malik with an offer to accept him into the gang if he murders an unruly Arab inmate, it is clear that this is not an offer he can refuse. Malik is made a lieutenant in the gang after committing the gruesome act – and we are not spared a single detail, from Malik’s agonising attempts to conceal a bare razor blade in his mouth to the pathetic gurgling screams of the unfortunate Reyeb.

Things do not improve for this unfortunate outsider, however, as he is slanted by the Corsicans (who call him ‘Arab’ and suggest he is only fit for belly-dancing and house-work), berated by the Arabic community in the prison for siding with the enemy, and haunted by Reyeb’s ghost as he lies alone in his murky cell. Malik teaches himself to read and, by carefully studying Cesar and the gang, learns to speak Corsican and slowly picks up the ins-and-outs of the gang’s operations. He also makes an ally in Ryad, a softly spoken man with the cold, dark eyes of a killer.

Malik works his way up the chain of command to become Cesar’s right-hand man and most trusted ally in the prison; and when Cesar organises for him to be released for one day (to check on Cesar’s interests on the outside) he uses the opportunity to start up a side-business moving vast packages of hasish with Ryad (who has since been released) between France and Spain. As Cesar becomes a more desperate and alienated figure in his cell, and powerful adversaries work up the courage to confront him, Malik benefits from all the new connections he is making.

One of the founding tenets of the Nouvelle Vague was an admiration for American film noir, and a mystical ability to inject that rigid genre with a flowing, intuitive, philosophical dimension. Melville, Chabrol, Godard, et al were open about their worship of Humphrey Bogart, John Huston, and the other legends of Hollywood noir; but they were all cineastes and academics who knew that the ‘camera-stylo’ could be used for so much more than Dashiell Hammett adaptations.

In ‘A Prophet’, Audiard has created an accessible and stomach-churning prison drama that the most cautious American viewer could enjoy. All the genre tropes are there – gang initiation, deceit, loyalty, criminal codes, corrupt authorities, car chases, gun battles – but these comforting and visceral moments only exist as sharp jabs to the stomach in what is actually a flowing, complex study of loneliness and masculinity. There is no attempt to validate Malik as a hero, he, along with every other character in the film, is a victim of the brutality they were born into. There is no hope, just a daily fight to survive and make tomorrow’s fight a bit easier. When Ryad develops a terminal disease, there is no despair or sadness shared between these two close friends, just an understanding that Ryad will be released from his bondage slightly sooner than Malik.

Having worked with some of the biggest stars in French cinema (namely Jean-Louis Trintignant, Mathieu Kassovitz, and Vincent Cassel) Audiard has chosen a relative unknown to lead this brutal character study. Tahar Rahim’s performance is without a doubt one of the most infecting and memorable performances of the year. He creates a perfectly conflicted and tragic figure in Malik: he is cold and toughened by a lifetime in the penal system, but he has a child-like vulnerability and a need for human connection. His friendship with Ryad is perfectly portrayed… a deep affection that can never be admitted by either party.

This is undoubtedly one of the finest films of the year. It is an inspiring proof that the genre conventions of American story-telling can be fused with the mystifying explorations of the human condition more present in European independent cinema, to create films that perhaps rise above both camps purely because they are capable of fulfilling the highest aims of culture and communication… to inform, educate, and entertain.