According to filmmaker Greg Barker, Sergio Vieira De Mello is “the most famous man you’ve never heard of.” Having spent his entire adult life working for the UN (he started in the office of the High Commissioner for Refugees after leaving the Sorbonne at the age of 21) Sergio became one of the most influential and renowned figures in global politics. He was one of Kofi Annan’s most trusted advisors, and was rewarded for his selfless passion and dedication with the office of High Commissioner for Human Rights in 2002.

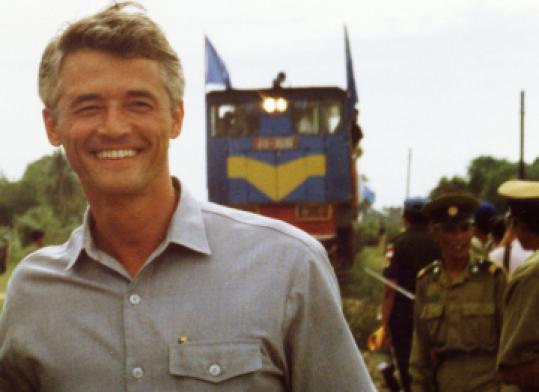

Sergio is probably the only man in modern politics to be referred to, globally, by his first name alone. Not even the Kennedy clan, so beloved and trusted at home, were referred to as ‘Bobby’ or ‘John’ outside the US. From the opening frames of the film, as Sergio flashes his famous grin, it is easy to get the measure of the man: he is enigmatic, charming, handsome, and effortlessly cool; but he is also selfless, and confident in a way that frees him from the urge to win people over with false promises or pompous shows of masculinity. He is the sort of man who could meet Ahmedinijad and George W. Bush on the same day and charm them both into a slightly warmer, less Hawkish, attitude towards global affairs.

Unfortunately, not even Sergio could prevent Bush’s illegal offensive against Iraq in 2003; and while most of the world, including the UN, wanted to distance themselves from the barbaric and thoughtless actions of the US and British governments, they realised that they had a responsibility to help clean up the mess. Of course, Sergio was the first name on everyone’s lips. In 1999, Kofi Annan had sent Sergio to see if he could fashion some sort of peaceful democracy in war-ravaged East Timor. Against all the odds, Sergio succeeded, and it is the only example in history of an occupational force actually helping to bring peace and prosperity to a war-torn region.

Sergio, after so many years living in dangerous territories from Bosnia to Cambodia, had seemed about ready to settle down. His first marriage ended badly, and he rarely had time to see his two sons. Having reached the position of High Commissioner, and finally falling in love again with a Brazilian economic advisor in East Timor, he was reluctant to risk throwing it all away. But a man like Sergio is bound by greater responsibilities than the average human. There are not many people who can claim that the world really needs them in a time of crisis, but Sergio is such a man, and so he took a four-month leave of absence from his post as High Commissioner to serve as Kofi Annan’s special representative in Iraq.

Sergio went about his business as usual. For the man who had negotiated with the Khmer Rouge in their jungle hideouts, Sergio was not scared to go out into the streets of Baghdad and speak to the people and find out what really needed to be done to help this country get back on it’s feet. Sergio had always been an advocate of treating those in need as human beings, rather than large groups of ‘refugees’ that needed to be herded like cattle.

Unfortunately, there has not been a single happy ending during the never-ending nightmare of Operation Iraq Freedom. On August 19, 2003, a truck bomb organised by Zarqawi (Bin Laden’s representative in Iraq) ploughed into the UN headquarters in Baghdad, right below Sergio’s office. Two US army reserves spent hours trying to save Sergio, but without any back up or equipment, they failed to recover his body, and he died buried in the rubble.

Barker’s film reveals the bombing within the first fifteen minutes of the film; and it is one of the most effective and thrilling pieces of documentary filmmaking I have ever seen. We cut back and forth between flashes of a truck speeding along a dirt track, and various interviews with people explaining exactly what was happening in the seconds leading up to the crash. This all builds up to a crescendo as we cut to a conference on the ground floor that was being filmed at the time of the explosion. The timing is perfect, we know what is about to happen but Barker holds off for just long enough so that when the explosion finally rips through the room, and the camera goes black for a few seconds, our nerves are shot to pieces and we feel physically and emotionally devastated.

Up to this point, we really don’t know much about Sergio, except to say that he is an important political and humanitarian figure, and we are more shocked than upset at the attack. But this is probably the most interesting element of this documentary: it is first and foremost a direct account of the attempts of two US army reserves to save Sergio and Gil Loescher (an advisor who was trapped with Sergio). We learn about Sergio’s blessed life through colourful and vibrant flashbacks, and they are all the more heartbreaking for seeing them as brief pockets of hope during the tense and harrowing attempts to save Sergio after the blast.

I did wonder if the film was going to stray into exploitative territory, and use Sergio’s death as a stick to poke the failures of the US occupation in Iraq. Director Barker is an American war correspondent made famous by his caustic examination of the world’s failure to act over the Rwandan genocide. While his integrity, intelligence, and passion have rightly never been called into question, I did wonder what he was getting at by making an entire feature documentary about one death.

But then I realised that Barker had ultimately found something almost hopeful and redeeming in this morbid and heart-breaking story. Even in his death, Sergio encapsulated the selflessness and calm optimism that he had exuded throughout his energetic life. As Barker writes in his director’s statement, “for all it’s tragedy, I ended up making a film that I think is ultimately about hope and the abiding resilience of the human spirit – even in the face of impossible odds. That’s what Sergio taught me, and maybe that’s a quality we can all use a little of right now.”

The key people in the film are the two US army reserves who trued to rescue Sergio (William von Zehle and Andre Valentine) and Carolina, his girlfriend who was present during the blast and refused to leave the site until his body had been recovered. It is Willim von Zehle’s account of the final moments, when they realised Sergio had passed away, that filled my eyes with tears. Von Zehle is one of those unassuming, soft spoken, and quietly intelligent Americans that doesn’t seem to fit with the global image of brash rednecks who never leave their own country save to blow up someone else’s. While Carolina, understandably, has dealt with her grief by speaking about Sergio is poetic and almost metaphysical terms, and Andre Valentino is a slightly irrational evangelist; it is von Zehle who provides the most gut-wrenching, frank account of events. The fact that such a reasonable man finally breaks down on camera and is forced to choke back his tears, speaks volumes about the effect Sergio had on mere mortals, even in his dying. It is also a genuinely powerful cinematic moment, and as I looked around me I noticed that I was not the only audience member gently wiping away the tears from the corner of my eye.

The film comes to a close as von Zehle reads aloud a letter that he felt impelled to write to Kofi Annan. In it he explains the courage, calm, and selflessness that Sergio exhibited in his dying hours. This humble fireman and reserve troop goes on to sum up everything Greg Barker wanted to say about Sergio: death is never easy or positive, but to die in a way that inspires hope in others, and immortalises your character in life, is surely a precious and rare thing.